The ‘Hebrides’ Overture by Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy

From one of the two original sketches of Mendelssohn’s dated 7 August 1829;

the other is a pen and ink drawing titled “A Look at the Hebrides and Morven”

Composers have for centuries been influenced by places abroad and cultures foreign, from the European dances of Bach’s suites, to the American-inspired string quartet, quintet and symphony by Dvořák. Felix Mendelssohn traveled far, directly influencing among others his “Italian” and “Scottish” symphonies. The ‘Hebrides’ Overture was a result of a visit to the Western Highlands, Scotland in 1829, and in particular to a “Solitary Island” (referring to the island of Staffa) and Fingal’s Cave. These various references lead to the work’s multiple titles: The Hebrides, The Lonely Isle, The Isles of Fingal and Fingal’s Cave. As a concert overture rather than an operatic one, it stands on its own as an orchestral work.

With the overture, Mendelssohn not only evokes the imagination of geography, but continues the introduction of programme-music heralded in Beethoven’s ‘Pastoral’ Symphony – and some might argue, making Vivaldi’s ‘Four Seasons’ strikingly ahead of its time. Scene painting was clearly the composer’s forte, with Wagner later saying “Mendelssohn is a landscape painter of the first order, and the ‘Hebrides’ Overture is his masterpiece.” A simple phrase brings us the motion of the ocean waves, eerie pedal notes in the winds ascend to the turbulence of orchestral crescendos and diminuendos, with timpani roars of thunder, and the eventual interplay of woodwinds and strings the battling elements of wind and sea. Going even beyond these, Mendelssohn revised the overture two years after its completion in 1830, saying that “the middle portion in D marked forte is very ridiculous, and the whole working-out tastes more of counterpoint than of train-oil, sea-gulls, and salted cod – it should be just the other way around.”

In the end, the impact of the overture, as with all great works, is that art goes beyond the capacity of words. When asked by family to describe the scene in the Western Highlands, Mendelssohn simply replied, “They are not to be described, only played about.”

Coincidentally, in its premier in 1832 the Hebrides Overture was also paired with works by Rossini, a combination which Mendelssohn himself found amusing, commenting that it “went splendidly, and sounded so droll amongst all the Rossini things.”

Sir George Grove ascribed the oasis towards the end to the “warmth and colouring” of Italy, where he completed the overture. But perhaps one does not have to go that far to find a bit of brightness; as Mark Ostyn who conducted the work at Pessoc’s inaugural concert in 1995 commented, “As might be expected of British weather, there is mostly stormy seas and shrieking winds, though with the odd patch of sunshine, as seen in the clarinet solo.”

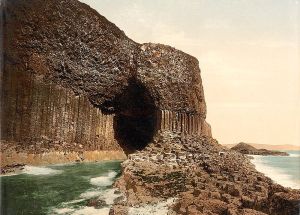

Fingal’s Cave with walls of volcanic basalt forming a hexagonal entrance

~ Andrew Filmer

with principal references to “Mendelssohn’s ‘Hebrides’ Overture. (Op. 26.)” by Sir George Grove and “Of Sea Gulls and Counterpoint: The Early Versions of Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture” by R. Larry Todd.

Leave a comment